Image 1 of 5

Frazier Park resident and architect, Max Williams, with Patric Hedlund, editor of The Mountain Enterprise, on August 20, reviewing documents about the Frazier Park Library building project. The paper trail appears to reveal that destruction of two 200-400-year-old heritage Valley oaks was caused by the construction company’s failure to fulfill its contract to follow the architect’s plan.

Image 2 of 5

The June 12 ‘Chainsaw Massacre’ of Frazier Mountain Park’s 400-year-old heritage oak.

Image 3 of 5

County’s architect in 2006 promising community that oaks on the site would be preserved.

Image 4 of 5

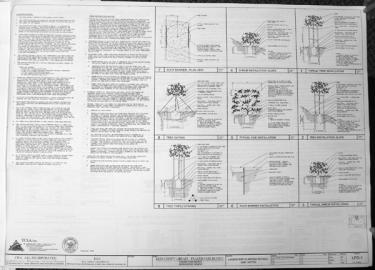

This document, titled LPD-1 details instructions from the architect, CWA, AIA Inc., about the tree fences required at the library construction site to protect and preserve Frazier Park’s heritage oak trees. These tasks are included in the project contract for which Kern county agreed to pay Tilton Pacific Construction over $4 million.

Image 5 of 5

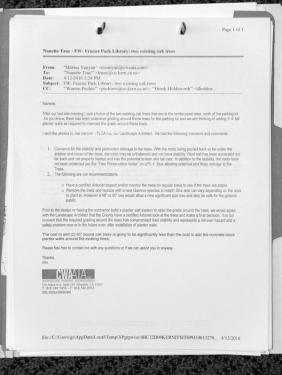

This April 12, 2010 document was called the “smoking gun” by architect Max Williams. In it, James Nardini, AIA points out that the oaks have been damaged due to grading and that the requirements for protection of the oaks had been detailed in the original plans, to which the contractor had agreed.

Firm Profits from Destruction of Heritage Oaks

By Patric Hedlund with Gary Meyer

On Tuesday, Aug. 24, it took less than 8 minutes for the Kern County Board of Supervisors to unanimously agree to all the items on their 2 p.m. consent agenda. There was no discussion. Among the items was Change Order No. 4 for $103,142 from Tilton Pacific Construction, the company that is building the new Frazier Park Branch Library.

The new library began as a project for which the community showed boundless enthusiasm. The festive groundbreaking ceremony last year is proof.

But that altered profoundly on Saturday, June 12. The roar of chain saws wielded by county workers lifted aloft by cranes woke the community at 7 a.m.

Two of the community’s treasured heritage oaks, one estimated to have lived 400 years, the other thought to be 200-300 years old, were being destroyed.

Community response was immediate. We have reported extensively about that.

In public meetings for five years Director of Kern County Libraries Diane Duquette and county architects had promised that those oaks would be preserved if the library was built at the site adjacent to the historic Frazier Mountain Park.

On June 15, county personnel met with the community and told them that the oaks were “diseased” and that they were growing on a “shear fault” and that they posed a liability that could “hurt somebody, or fall on a child,” if they were allowed to remain standing where they had stood for hundreds of years over many generations of children. Two weeks later we published the arborist’s report which misidentified the species of the trees, calling them Blue oaks instead of Valley oaks. We interviewed the arborist, who agreed they were Valley oaks, then apologized, saying, “I was upset by what had happened to the trees.” He reported that construction grading had mutilated the roots.

We photographed the remaining oaks at the site and the construction staging area used by Tilton Pacific. There were no tree fence barriers in place. Equipment and supplies were stored under the trees, up to the trunks, compacting the earth, which can suffocate the roots of oak trees.

On Tuesday, June 29, numerous attempts were made to talk with Tilton Pacific Construction. The Mountain Enterprise called the corporate office in Rocklin, CA and were told that only the supervisor of the library construction project could talk. We called Robert Santana’s cell phone three times. He did not answer. Three attempts were made at the site office in Frazier Mountain Park. Our reporter knocked at the office door and was told Santana was too busy to talk. We asked for a time at which that would be possible. He told The Mountain Enterprise reporter that he did not want to speak with the newspaper about the oak trees.

The Mountain Enterprise made a public records request to examine documents associated with the library project and the removal of the oak trees.

On August 20 we were greeted by Kern County Contract Specialist Nanette True in the conference room of the Kern County General Services Department. We spent five hours reviewing documents.

We found that the architect’s plans carefully specified the methods the contractor who won the bid must follow in order to protect the oaks. [See below for Tree Protection notes] Document LPD- 1 in the project plans was quickly pulled out of the stack by Frazier Park architect Max Williams, who accompanied us to Bakersfield to review the records.

We checked to see if there was an exclusion in the contract, by which the contractor might have removed those tasks from the bid. Williams scanned the contract. “There is no exclusion,” he said.

That would mean that the steps outlined on LPD-1 were encompassed within the roughly $4 million job won by Tilton Pacific Construction.

In a file from Warren Pechin, a construction services engineer, we found that a change order had already been authorized paying $1,104 for providing “all labor, material and equipment to remove the existing tree stumps in two locations.”

Another Tilton Pacific proposed change order—slated to be before the board of supervisors on August 24, four days after our records review. That document was titled Proposed “Change Order No. 4.” It would award Tilton Pacific $103,142. Within that was “Item 1) Provide all labor, material and equipment to complete stump removal” for $9,968. Also within that change order was “Item 7) Provide all labor, material and equipment, on a time and material basis, mulch and temporary barriers around the drip lines of two oak trees in the staging area of the Park” for an added $60,046.

So, it appeared that at least $70,014 of that change order was a request for payment for something Tilton Pacific had already agreed to do under the original contract and for removing stumps of trees they had destroyed by failing to deliver as agreed in their contract.

On Friday, Aug. 20 at 1 p.m. The Mountain Enterprise called Kern County Supervisor Ray Watson while in the Kern County General Services conference room, a few floors below Watson’s office.

His lead aide, Christy Fitzgerald, answered the phone. We asked for Supervisor Watson and were told that he was unavailable. Editor Patric Hedlund told Fitzgerald that we were looking at documents that made the change order on the agenda for approval in the following week’s meeting appear to be a double billing. We asked if they would like to see them. Fitzgerald said, “Ray got the agenda last night. I’m sure he knows all about everything that is on it.” We thanked her for her time and said good-bye.

On Tuesday, Aug. 24 at 2 p.m., agenda item 20-CA came up for a vote with other consent agenda items and was not removed from the consent roster for discussion. It was passed without a single question. Supervisor Ray Watson chaired the meeting.

On Wednesday, Aug. 25, Supervisor Ray Watson was asked in person by The Mountain Enterprise why the board of supervisors voted to approve a new change order for removal of the stumps of the heritage trees and creation of protective fencing and mulching when documents show the contractor was originally required to protect the oaks from the type of damage that necessitated their removal. Watson said he would like to see the documents and discuss the matter after reviewing them.

On Wednesday, Aug. 25, we called the corporate office of Tilton Pacific Construction and were referred to Greg Hall, who introduced himself as the operations manager. He listened to our question and said he would refer us to county personnel. We said our goal was to understand Tilton Pacific Construction’s reasons for submitting the change order for the tree protection and mulching, when those items were part of the original contract and specifications.

We referred him to the Change Order 4 and the architect’s LPD- 1. He said, “Why didn’t you ask us earlier?” We told him of our efforts to speak with the company earlier. He, too, said he would like to review the documents, and that he did not know if he was authorized to speak.

Next week, we will continue this report.

Tree Protection Notes

By CWA Architect (in Document LPD-1)

–emphasis added–

1. “Protected Zone” for existing trees: before beginning any demolition or construction operations, the contractor shall install temporary fencing around all existing trees within the construction zone that are to be saved.

The fence shall be installed no closer to the tree than the edge of the tree’s protected zone, generally defined as the area beginning five feet outside of the trees dripline and extending towards the tree (or as far away from the trunk as practicable). The fencing shall be of a material and height acceptable to the landscape architect.

All contractors and their crews shall not be allowed inside this “protected zone” nor shall they be allowed to store or dump foreign materials within this area.

No work of any kind, including trenching, shall be allowed within the protected zone except as described below. The fencing shall remain around each tree to be saved until the completion of construction operations.

2. Temporary Mulch: To alleviate soil compaction in anticipated areas of high construction traffic, and only where fencing cannot be set five feet outside of the dripline, the contractor shall install a layer of mulch, 9”- 12” thick, over all exposed earth from the tree trunk to 5’ outside of the dripline. This layer shall be maintained at all times during construction. When planting operations are completed, the mulch shall be redistributed throughout all planting areas in a 3” thick “permanent” mulch layer.

3. Necessary Work: When it becomes necessary to enter the “protected zone,” such as for fine grading, irrigation installation and planting operations, the contractor shall strictly adhere to the following rules:

A. Every effort shall be made to preserve the existing grade around protected trees in as wide an area as possible.

B. Trenching within the protected zone of existing trees shall be performed by hand, and with extreme care not to sever roots 1-1/2” in diameter and larger. Where roots 1-1/2” in diameter and larger are encountered, the contractor shall tunnel under said roots. Exposed roots that have been tunneled under shall be wrapped in wet burlap and kept moist while the trench is open.

C. Where roots 1-1/2” in diameter or larger must be cut due to extensive grade changes, those roots must be exposed by hand digging and cut cleanly. Ragged cuts generally do not heal properly and may leave the tree open to pests and pathogens.

D. Where trenching near trees has already occurred from previous construction operations, the contractor shall make every effort to confine his trenching operations to the previously-created trenches, while adhering to the conditions set forth in 3-B.

4. Potential Conflicts: the contractor shall notify the owner and arborist should any potential conflicts arise between these specifications and/or large roots encountered in the field and construction operations. The contractor shall not take any action in such conflicts without the arborist’s written approval. The arborist shall have final authority over all methods necessary to help ensure the protection and survival of existing trees.

[Items 5 and 6 dealt with pruning and landscape irrigation.]

This is part of the August 27, 2010 online edition of The Mountain Enterprise.

Have an opinion on this matter? We'd like to hear from you.