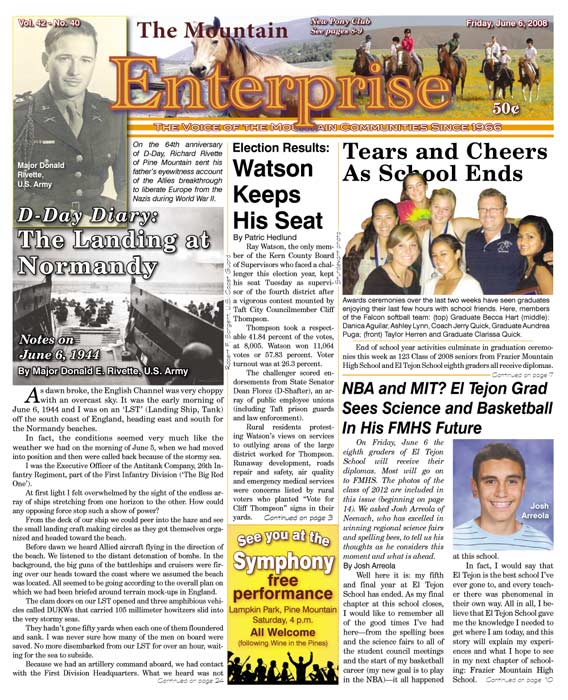

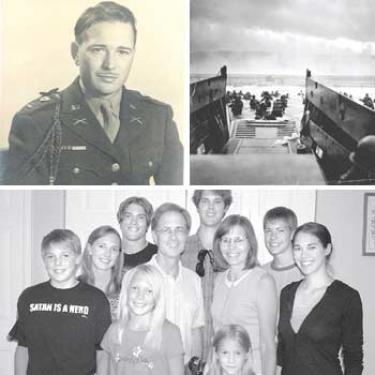

On the 64th anniversary of D-Day, Richard Rivette of Pine Mountain sent his father?s eyewitness account of the Allies breakthrough to liberate Europe from the Nazis during World War II. Top left, Donald E. Rivette in uniform. Top right, a photograph of a LST landing by Robert F. Sargent, U.S. Coast Guard. Bottom, the Rivette family of Pine Mountain is proud of their grandfather?s service (front): Jason, Rachel and Carissa; (middle row): Crystal, Rick, Linda and Tiffany; (back row): Jeremy, Ryan and Jonathan. Jonathan and Jason are students at Frazier Mountain High School, Rachel and Carissa are students at the Pine Mountain Learning Center.

Notes on June 6, 1944

By Major Donald E. Rivette, U.S. Army

As dawn broke, the English Channel was very choppy with an overcast sky. It was the early morning of June 6, 1944 and I was on an ‘LST’ (Landing Ship, Tank) off the south coast of England, heading east and south for the Normandy beaches.

In fact, the conditions seemed very much like the weather we had on the morning of June 5, when we had moved into position and then were called back because of the stormy sea.

I was the Executive Officer of the Antitank Company, 26th Infantry Regiment, part of the First Infantry Division (‘The Big Red One’).

At first light I felt overwhelmed by the sight of the endless array of ships stretching from one horizon to the other. How could any opposing force stop such a show of power?

From the deck of our ship we could peer into the haze and see the small landing craft making circles as they got themselves organized and headed toward the beach.

Before dawn we heard Allied aircraft flying in the direction of the beach. We listened to the distant detonation of bombs. In the background, the big guns of the battleships and cruisers were firing over our heads toward the coast where we assumed the beach was located. All seemed to be going according to the overall plan on which we had been briefed around terrain mock-ups in England.

The clam doors on our LST opened and three amphibious vehicles called DUKWs that carried 105 millimeter howitzers slid into the very stormy seas.

They hadn’t gone fifty yards when each one of them floundered and sank. I was never sure how many of the men on board were saved. No more disembarked from our LST for over an hour, waiting for the sea to subside.

Because we had an artillery command aboard, we had contact with the First Division Headquarters. What we heard was not It was now 0900 hour, two and a half hours after the first boats set out, and there was no confirmation of a landing yet. There was a very subdued atmosphere aboard ship, as we stood around the deck with not much to do but wait and hope for the best.

We were all certain that the invasion would eventually succeed by the sheer mass of troops committed to the attack, but more anxiety came over us as the morning wore on without any good news.

At about 0930, the sea seemed to calm a bit and several more DUKWs were disgorged from the bow of the LST. We watched these swim away in the distance and most seemed to stay afloat.

About 1000 hours a destroyer went charging past us toward the shore, fired several shells at the beach and then quickly withdrew. Our LST was five miles out and we were too far to make out any activity on the beach. We felt a little more secure on this landing than the one in Sicily where our LST was singled out by a German dive bomber and a direct hit was scored on the bow doors, making them inoperable. We had to be pulled ten miles out and off-loaded into smaller craft. The LST next to us, with the unlucky number 313, received a direct hit and exploded and burned with high casualties. We remembered this incident as we scanned the skies for enemy aircraft.

In the First Infantry Division sector, the 16th Infantry Regiment had been selected for the initial assault unit, followed by the 18th Infantry Regiment and then the 26th Infantry Regiment.

My regiment, the 26th, was not due to land until the afternoon, a situation we greatly appreciated. Late in the morning, about 1100 hours, we saw a flight of B-24 bombers overhead, returning to England. Suddenly, a German fighter plane appeared out of the sky and shot down one of our aircraft. Immediately, one of our B-24’s peeled off, went after the German plane and shot it down. Every soldier and sailor in the whole convoy seemed to stand up and cheer as in a football stadium.

Around 1200 hours First Division Headquarters confirmed that we had troops ashore but as yet not broken out from the beach. Our schedule for landing was continuously being pushed back. Initially, it was around 1300 hours. Now it was 1400 hours, and then 1600 hours.

As our ship began to move closer to the beach we could make out a column of tanks and other vehicles lined up on the shore but not moving. We could also make out intermittent bursts of artillery shells falling on the column. Late in the afternoon we received word that the Division had finally broken through the beach defenses and that part of the 26th Infantry Regiment had landed. Our company was to wait until D+l, the next morning, to land.

The concern over enemy aircraft attacking the convoy was eased as we saw continuous cover of allied aircraft flying over us at all times.

Night time, however, was a little different. All ships were ordered to be in complete blackout and for good reason. All night the enemy flew bombing missions over the convoy, dropping bombs indiscriminately, but with little apparent effect.

The Nazi planes were easily identifiable as their engines had a different sound. In fact, one plane given the name of “Night Check Charlie,” sounded very much like an outboard motor. We heard this plane for a week as we moved inland.

Our LST touched down at dawn, landing just opposite the large draw on the Easy Red Sector of Omaha Beach. All up and down the beach we saw tanks and other vehicles stuck in the sand or destroyed by enemy mines or gun fire.

Other debris including hedgehogs, barbed wire, wrecked landing craft and all sorts of equipment littered the beach. The Graves Registration units had been busy throughout the night and bodies were piled in neat rows like cordwood. It looked like we had lost half the assault wave.

I stepped off the ramp of the LST and went up to my waist in the water. As our vehicles came off the ship we drove up the draw along a path cleared of mines and assembled just below the last hill. We were not too sure how far our troops had been able to push inland, but it seemed secure.

Captain Bidwell Moore, my company commander, sent our three antitank platoons—each with three 57mm antitank guns, towed by armored half tracks—off to join our infantry battalions who were now in the attack, while I set out to locate the Second Battalion, 26th Infantry, Command Post. There I saw eight or ten wounded enemy prisoners, waiting to be attended to at the battalion aid station. They had an oriental look about them. We later learned that they were from the German 352nd Infantry Division, recruited from somewhere in Russia.

Following up our daytime attacks, we made a series of night attacks reaching Caumont, fifteen miles from the beach, in five days. There we stayed—out on a point for almost a month while we waited for the Second U.S. Infantry Division on our right and the British on our left to catch up with us.

When I returned home as a captain to Ann Arbor, Michigan in May of 1945 to see my dying mother, I swapped stories with my old boyhood friend, First Lieutenant Robert Lavey, who had flown B-24s in Europe.

He told me that he too would have been promoted to captain if he hadn’t broken formation to shoot down a Nazi plane that had just shot down his buddy over the beaches of Normandy on D-Day! In fact, he said that he was lucky that he had not been court marshaled for breaking formation that day!

Donald Ector Rivette was born in Dearborn, Michigan in May of 1918. He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant of Infantry in 1941 from the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) Department of the University of Michigan, and was one of the first soldiers who trained in the newly-created American airborne unit that eventually became the 502nd Parachute Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division.

Donald broke his leg during a jump at Fort Benning, Georgia but afterward was assigned to the First Infantry Division where he served throughout World War II in North Africa, Sicily, Normandy, France, Belgium and into Germany.

In Belgium he was ambushed and ordered to surrender by Nazi paratroopers behind friendly lines. He refused and opened fire with the machine gun on his jeep, killing eighteen enemy soldiers and becoming badly wounded in both legs. He received the Silver Star for gallantry in action for this incident. At the Battle of the Bulge he commanded the Antitank Company of the 26th Infantry Regiment at the town of Dom Butgenbach Belgium, helping to stem the tide of the Nazi assault. One of his soldiers, Corporal Henry Wamer, received the Congressional Medal of Honor in this battle. Major Rivette retired from the Army in 1964 after twenty-two years of service, his last four years spent as an assistant professor of Military Science at the University of Georgia. He died of heart failure in Alpharetta, Georgia in February 1999 when he was 80 years old.

One of his sons, Rick Rivette, lives in Pine Mountain.

This is part of the June 06, 2008 online edition of The Mountain Enterprise.

Have an opinion on this matter? We'd like to hear from you.